#How Wong

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“B 3649 Procession Wong Fong, Chinatown, S.F. Cal.” c. 1884-1888. Photograph by Isaiah West Taber. Taber captured a street scene showing a procession of Chinese residents walking down a street, carrying lanterns and banners. The exact date of the photograph is not known, but contemporary newspaper accounts reported that “thousands” of non-Chinese viewed the parade as least by 1887. (“Procession Wong Fong” reposes in several collections, including the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley.”

The Wong Fong Parades of Old Chinatown

Long before Chinese dragons became a highlight of San Francisco Chinatown’s Lunar New Year parade—the largest in North America—they made their way through the streets for the Wong Fong or Hau Wong celebration, a tradition dating back to the late 19th century.

Hau Wong or Hou Wang (Chinese: 侯王; canto: “hau4 wong4”; pinyin: “Hóu Wáng”), which can be translated literally as “Prince Marquis” or “Holy Marquis,” is the title usually accorded to General Yeung Leung-jit [zh] (楊亮節; 杨亮节; canto: “joeng4 loeng6 zit3”; pinyin: “Yáng Liàngjiē”). Despite his failing health, this reputedly loyal and courageous general chose to remain in the army to protect the last emperor of the Southern Song dynasty when the Song court fled southwards and took refuge in Kowloon.

The San Francisco Chinese community’s public and colorful reverence for the deified general prior to 1906 attracted the interest of not only the city’s press but also pioneer photographers such as Isaiah West Taber.

The city’s newspapers frequently published reports about the Chinatown community’s public veneration of Hau Wong. For example, on September 26, 1884, the Chinatown community of San Francisco staged an extraordinary parade and celebration in honor of the 2,000th birthday of “How Wong,” a revered general of the “Canton District,” as the Daily Alta California newspaper described in its issue of the following day. The event had been meticulously organized by the Yeong Wo Company, one of what the reporter described as the “six influential district associations in America.”

The Yeong Wo Association (陽和會館; lit. “Yeong Wo Hall”; canto: “Yoeng4 Wo4 wui6 gun2“) is one of the original district associations that formed the Chinese Six Companies in San Francisco around 1850, serving as a key organization representing Chinese immigrants from Heungshan (now Zhongshan) County in Guangdong Province. As part of the Six Companies, the Yeong Wo played a vital role in advocating for the rights and welfare of Chinese immigrants, providing social services, mediating disputes, and offering financial assistance. It also helped members navigate challenges such as anti-Chinese discrimination and restrictive immigration laws. Today, the Yeong Wo continues to operate as a significant cultural and community organization, preserving Chinese heritage and supporting the Chinese American community.

Detail from the “vice” map commissioned by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in July 1885 (from the collection of the Chinese Historical Society of America).

Contemporary directories indicate that the Yeong Wo moved from 727 to 730 Sacramento St. in 1881, and its acquisition of new headquarters and temple facilities, accessed by a courtyard from the north side of Sacrament Street into a mid-block space (as shown by the city’s 1885 Chinatown map), undoubtedly played a role in its sponsorship of the Wong Fong festivities.

“Scene in the Joss House” from the September 22, 1903, issue of the San Francisco Call newspaper. The image purported to be the shrine of Hou Wong used in the Wong Fong celebratory parade of that year. How Wong or Hou Wang (Chinese: 侯王; canto: “hau4 wong4”; pinyin: “Hóu Wáng”) can be translated as “Prince Marquis” or “Holy Marquis,” and represented the title usually accorded to Yeung Leung-jit [zh] (楊亮節; 杨亮节; canto: “yoeng4 loeng6 zit3”; pinyin: “Yáng Liàngjiē”). Despite his failing health, this reputedly loyal and courageous general remained in the army to protect the last emperor of the Southern Song dynasty when his court fled southwards and took refuge in Kowloon.

The idol of Wong Fong was housed in the Yeong Wo’s temple on Brooklyn Place (a.k.a. Alley). Early in the morning, he was ceremoniously placed in a sedan chair, and by 10 o’clock, a grand procession of nearly 1,000 Chinese residents had assembled to escort him to a theater. Leading the procession was Captain Ned McLaughlin, who carried out his duties as Grand Marshal with a flourish that rivaled the most distinguished drum-major. Behind him rode a Chinese gong band in horse-drawn carriages, followed by an honor guard composed of four men armed with Springfield rifles, four wielding spears, and four carrying crossbows. Encircling Wong Fong, the guards presented a display of martial prowess.

The parade featured a striking array of banners and flags, including both the Stars and Stripes and the imperial dragon flag, carried side by side. Participants of all backgrounds—men and women, young and old, adorned in elaborate garments—marched alongside intricate pagodas, floral arrangements, and other elaborate displays. Among the most remarkable sights was a long wooden beam mounted on a pivot, with a Chinese youth at each end, dressed in armor and wielding swords. As the beam spun, the two performers engaged in a mock battle, reenacting scenes from the warrior exploits of Wong Fong.

Another dramatic highlight was an immense dragon, stretching fifty feet in length. Hidden within its brilliant-hued body, a dozen men manipulated the creature’s movements, their feet barely visible beneath its undulating form. The dragon surged across the street in a serpentine motion, while the bearer controlling its head made the enormous jaws snap open and shut, producing a hissing sound that added to the spectacle.

“Chinese Parade with the Dragon” c. 1882–1892. Photographer unknown (from the Marilyn Blaisdell collection). This elevated view toward the north on Stockton Street shows a dragon-led parade moving south on Stockton. Men (for whom Victor Nee would describe almost a century later as the “bachelor society”) comprise most of the crowd at street level. Other onlookers appear from rooftops, windows and the store awning in the center of the photo. The porch with iron railing at far left is part of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. This photo, and another photograph taken by A.J. McDonald show parade participants carrying a portable gate preceding the main procession of the dragon. Two Chinese ideograms across the top of the gate read 禹門 (lit. “Yu Gate;” canto:”Yu munh”). The 禹 character referred to a near-mythical sage-king of ancient China, known as Yu the Great (大禹; canto: “dai Yu”) or “Yu the Engineer.”

After weaving through the city’s main thoroughfares, the procession arrived at the Grand Theatre on Washington Street. There, How Wong’s effigy was placed in a position of honor while the company performed a dramatic reenactment of his legendary deeds. The festivities continued into the evening with a grand feast at the Yeong Wo’s temple, and the celebration repeated the following morning before How Wong was returned to his resting place—until his next birthday.

Chinese parade with a dragon east down Washington Street and past pawnshops and the Grand Theatre in Chinatown, c. 1882. Photographer unknown. The dragon appears identical to the one shown in the preceding series of photos of the Stockton Street parade. However, unlike the apparent Sacramento Street route taken in the preceding series by Taber and McDonald, this procession is moving east down Washington toward Dupont Street (as confirmed by the inscription on the street lamp at lower left corner of the image).

The public veneration of Hau Wong returned the following year, when Chinatown mounted an even more lavish event. In a September 17, 1885, issue of the Stockton Mail newspaper, a correspondent filed a “San Francisco Letter” which contained an eyewitness account of that year’s Hau Wong parade.

The dispatch from San Francisco was also notable for including one of the first descriptions of Chinese brandishing not only traditional Chinese ceremonial weaponry but also firearms, indicating that the city’s Chinese “have been well supplied with arms and ammunition in expectation of an attack by the followers of Dr. O'Donnell,” who had been advocating for their violent expulsion.

Although it remains unclear if the Wong Fong celebration went on a hiatus, it made the news again two years later on a vibrant day in 1887, when San Francisco's Chinatown was transformed into a spectacle of color and sound. Businesses closed their doors, and, as the Daily Alta California reported on September 24, “the dragon flag flew from every staff in the Mongolian quarter” in honor of the “birthday of Tang Wong, the presiding deity of the Yeong Wo Company.” The Wong Fong parade, according to the newspaper, represented the culmination of six months of event preparations by the Chinese

Headlines from the Daily Alta California, September 24, 1887

In a foreshadowing of larger parades 66 years later, Chinatown’s streets filled with a sea of onlookers, “thousands of white people” joined Chinese, eager to witness the Wong Fong parade. Dragon flags waved from every staff, and the air buzzed with anticipation.

The procession commenced at around 11 a.m. with a grand display of traditional Chinese culture. Leading the parade were striking banners and elaborately decorated floats. A magnificent, parti-colored paper dragon, stretching an impressive 170 feet, snaked its way through the streets, carried by fifty-two men. Miniature pagodas, adorned with burning incense and floral offerings, were paraded before the dragon. The men carrying the dragon wore distinctive hats resembling inverted washbowls, embellished with golden-colored hair and gold buttons.

“Procession of the Dragon” c. 1892. The artist for this illustration, based closely on photo “B3649 Procession Wong Fong” by Isaiah West Taber, inserted a flag for dramatic effect. The flag appears absent not only from Taber’s original image and derivative illustrations, but also other photos taken of the same parade on Stockton Street. The second illustration, “Procession Wong Fong – The Most Representative Public Celebration Among the Chinese in San Francisco” 1895, is a reprint of a painting by “Thulstrup from photographs by Taber” and published as a magazine illustration. The illustration appears based on photo B 3649 by Isaiah West Taber and perhaps variants of the same Wong Fong parade proceeding south on Stockton Street.

Taber’s photo and the illustrations of the same event confirm the interest in viewing the Wong Fong parade by white Chinese San Franciscans, foreshadowing the Chinatown community’s invitation to, and participation of, non-Chinese in the New Year celebration of 1953.

Following the dragon came a captivating array of participants. Maidens, dressed in their finest attire, rode gracefully on horseback. Priests, clad in richly colored robes, walked solemnly in the procession. Other participants carried large, ornate lanterns, adding to the visual splendor. Among them were men identified as descendants of Mandarins or members of the "blue blood" class, and students representing the Chinese Empire, each group distinguished by unique tablets. A particularly striking figure was a large, fantastically constructed serpent with a large head, horns, bright eyes, and a wide-open mouth.

Chinese parade on Dupont Street, no date but prior to 1906. Photographer unknown (from a private collection).

The parade also featured warriors carrying an assortment of weapons, including blubber-knives, long guns (described as “O’Donnell rifles” to dissuade interference by anti-Chinese agitators led by the ten-city coroner), tridents, machetes, and axes. They marched with a spirited air, drawing cheers from the crowd. A maiden and a youth rode in a wagon, and two young boys engaged in mock combat with wooden spears. Before the dragon, several priests walked, periodically attempting to place golden balls into its mouth, seemingly as an offering. The crowd watched intently as the dragon appeared poised to consume one of the worshippers.

Chinese bearing traditional infantry weapons prepare to march in a San Francisco parade. No date. Photographer unknown (from the collection of The Bancroft Library). Newspaper accounts of parades in pre-1906 Chinatown frequently reported on the traditional Qing-era weaponry displayed in community processions and parades.

The Daily Alta article significantly recites that the 1887 parade paused at the Yeong Wo’s “newly constructed” temple on the third floor at 730 Sacramento Street, which suggests that the association had recently refurbished its temple premises, although it had occupied its quarters on the north side of Sacramento since at least 1881.

After arriving at the Yeong Wo’s building, priests entered the building to install the “Pak Seek Tan Wong” into its new place of worship. The dragon was ceremoniously brought to rest amidst lamentations and the sounds of tin-pan music. Two chiefs prostrated themselves before an image representing the "sender of rain," seemingly oblivious to the onlookers. After a period of kneeling, one of the chiefs threw a piece of curved wood, inscribed with Chinese characters, into the air, signifying the conclusion of the day's festivities. Incense filled the air, and the sounds of firecrackers echoed through the streets as merchants burned them in large quantities.

The Daily Alta California followed up with another report about a second day of Wong Fong-related festivities in its September 25, 1887, issue. Again, the interest displayed by non-Chinese in the parade’s pageantry was significant.

From the Daily Alta California, September 25, 1887.

Two years later, the Daily Alta California provided over the course of three days’ coverage (September 2-4, 1899) another rich account of the feast of Wong Gow [sic] or Hau Wong, a celebration of what the newspaper referred to as the “Chinese God of Charity” in San Francisco’s Chinatown.

On the first day of the 1899 event, organized by what the reporter mistakenly referred to as the association of “Yung Wo”province, notably involved feeding thousands of people, including impoverished Chinese residents and American transients, at various locations throughout Chinatown. The main distribution of food took place at the Yeong Wo’s 730 Sacramento Street building, where apparently no one was turned away. Sidewalks were transformed into banquet tables, accommodating the large crowds seeking free meals.

During the festivities, many eating-houses were decorated with lanterns, fans, rugs, and images, creating an elaborate and artistic display. In addition to the charitable feast, the Yeong Wo planned a grand procession to celebrate their annual harvest festival. The parade was scheduled to move through the principal streets of Chinatown, with rumors that it might extend onto Kearny Street. The event featured josses, banners, human figures, and a large dragon, which had been expanded to sixty feet with additional details since its previous appearance. A small army of Chinese men in traditional dress carried the dragon, followed by performers skilled in acts such as tambourine and kettledrum playing.

The newspaper reported on September 3 that the parade was to begin at 10 a.m. from the corner of Stockton and Jackson Streets, with expectations of a successful and vibrant celebration following days of festivities.

On the following day, the Daily Alta California described the September 2 parade the grand parade in Chinatown led by the American flag and accompanied by gong-pounders, flute players, and a large joss representing “Wong Gow.” A paper dragon, described as the deity’s deadly foe, was also featured prominently. Crowds filled the sidewalks, rooftops, and windows along the parade route, with Chinatown decorated in colorful lanterns and filled with the aroma of roast pork and garlic.

Before the parade began, the streets were packed with participants, ensuring that nearly every Chinese resident in the city, from rag-pickers to boarders, was in attendance. At 10 o’clock, the march commenced down Stockton Street to Sacramento, proceeding to Kearny, Commercial, Dupont, and Clay, before weaving through Chinatown’s smaller lanes. The parade was led by three Chinese men, followed by a woman riding a slow-moving horse. Behind them, thousands of participants, both on foot and horseback, dressed in bright traditional clothing, moved in rapid succession.

The newspaper printed a third story in its issue of September 4, 1889, that the Yeong Wo repeated the parade it had held on Monday, September 2. On the second day of festivities, thousands of spectators gathered to witness the parade, which was marked by the usual fusillade of firecrackers and an atmosphere of excitement throughout Chinatown. The procession again began around 10 a.m. in front of a joss house on Washington Street. The line of parade participants marched up Washington to Stockton, then proceeded south on Stockton to Sacramento, onto Dupont, and through the principal alleys and streets of Chinatown.

The event lasted until approximately 4:30 p.m., when the participants gathered at a house on Washington Street to conclude the celebration with worship. Following the religious rites, the dragon was ceremonially laid away. Throughout the parade, thousands of onlookers had lined the streets, observing what the article referred to as the “queer actions” of the Chinese participants. The event also attracted a significant number of European visitors staying in the city, who reportedly expressed surprise at the manner in which the Chinese community celebrated its festivals.

As usual, the highlight of the parade was an enormous dragon carried by 100 men. The dragon was adorned with three glaring eyes, a red nose, and green paint with tinsel. A Chinese warrior walked ahead of it, pretending to attack the creature with a spear, causing it to roll its eyes and open its mouth. At the conclusion of the parade, the dragon was taken to a Chinese theater, where a special performance was held in its honor. The newspaper notes that the procession was scheduled to be repeated the following morning.

The Yeong Wo Association apparently continued How Wong celebrations in succeeding years. In 1903 the San Francisco Call published its account of what had become an eight-day festival in Chinatown:

Unfortunately, no widely available records appear to exist, specifying exactly when the Yeong Wo Association stopped holding elaborate celebrations of Hau Wong in San Francisco’s Chinatown after 1903. ��More than a mere spectacle the Wong Fong parades represented assertions of cultural identity during a period of significant adversity for Chinese Americans. By honoring How Wong, the community reaffirmed its connection to the ancestral homeland while showcasing Chinatown’s resilience and unity. The elaborate festivities not only celebrated a historical deity but also served as a vibrant expression of Chinatown’s enduring spirit and pride.

#Yeong Wo Association#Wong Fong parade#Hau Wong#How Wong#Hou Wang#Wong Fong dragon#Isaiah West Taber

1 note

·

View note

Text

aeon I drew for a friend a while ago :)

#replaying re4r with my buddy and remembering how much I like them#aeon#ada wong#leon kennedy#leon s kennedy#resident evil#re4#resident evil 4#resident evil fanart

490 notes

·

View notes

Text

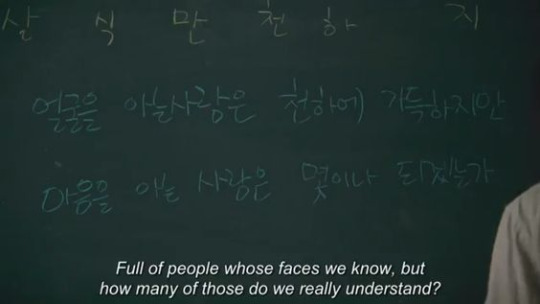

"IF THERE'S AN EXTRA TICKET... WOULD YOU GO WITH ME?"

花樣年華 In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai // Marie Howe After the Movie // 花樣年華 In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai // Shane McCrae In the Language of My Captor (via @geryone) // NCT U - WITHOUT YOU // 花樣年華 In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai // Ann Packer The Dive from Clausen's Pier // Becca de la Rosa & Mabel Martin Mabel: Matryoshka // Mitski Nobody // 花樣年華 In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai // Madeline Miller The Song of Achilles // unknown // Nicole Homer Underbelly // 花樣年華 In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai // @filmnoirsbian // 花樣年華 In the Mood for Love (2000) dir. Wong Kar-wai

#on yearning#on love#on heartbreak#in the mood for love#花樣年華#wong kar wai#maggie cheung#tony leung#web weave#web weaving#poetry parallels#poetry compilation#poem#spilled poetry#spilled thoughts#words#dark academia#spilled ink#writing#dark academia quote#dark academia poetry#poetry#marie howe#shane mccrae#nct#nct u#ann packer#mabel#mabel podcast#becca de la rosa

672 notes

·

View notes

Text

my piece for the @remembrancezine :)

#re2#resident evil 2#re2 fanart#leon kennedy#ada wong#digital art#artists on tumblr#art#illustration#remembrance zine#tyrant#mr. x#this was genuinely so fun to do and i love how it came out#it's like an updated version of the drawing of leon at the vending machine i made a couple years ago!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

mercenary’s scar

#art tag#based on that cracked porcelain trend ppl are doing on twt#and as adapilled as i am it got me thinking about her lore in re2… how she’s chipped and cracked until#she is made to work and pay. im so normal. im so normal she was ONLY TWENTY FOURRR#resident evil#resident evil 4#ada wong#capcom#video games#illustration#wanted to make this rlly melancholy and i think i pulled it off :]#re2 remake#re2make#resident evil fanart#re2 ada#re2 1998

726 notes

·

View notes

Text

liar liar pants on fire

#we all know how’s it gonna end#that is my only comfort right now#they absolutely nail the kicked puppy look#jack and joker u steal my heart#jack and joker the series#jack and joker#jack & joker#jackjoker#jackjoke#yinwar#yin anan#yin anan wong#war wanarat#veemark#love mechanics#thai bl#thailand#bl series#bl drama#thai bl drama#thai drama

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

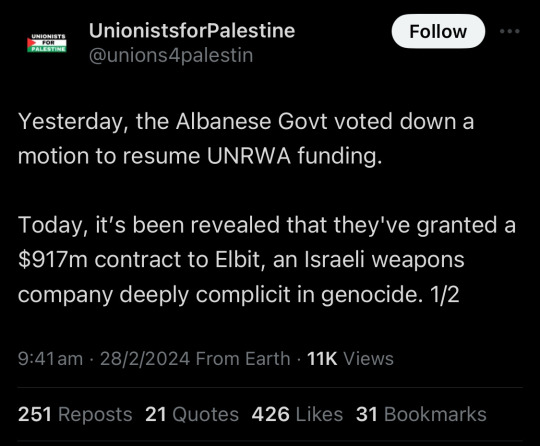

FOR AUSSIE FOLLOWERS - the Albanese government continues to actively perpetuate genocide in Palestine.

In case you haven’t been keeping up, recently;

- Albanese attended a private Katy Perry party funded in part by a prominent Israeli businessman.

-Albanese hasn’t released a single statement pertaining to the NSW policeman who brutally murdered two gay men just before NSW Mardi Gras, nor has he reigned in the NSW police commissioner who treated queer people not wanting police at pride following this tragedy as a major insult.

-Albanese’s office claims they haven’t received any emails asking the Australian government to not support genocide but is actively hanging up on calls.

While taking strong action now, it’s important to recognise and remember for future elections just how Labour sees its constituents.

RELEVANT LINKS FOR SOLIDARITY WITH PALESTINE

#meanwhile penny wong is wringing her hands and saying for the million time how ‘concerned’ she is about Palestinian lives#:((( what a shame penny really wish you were in a position where you could make some change in that direction#oh wait#fuck all of them#free palestine#palestine#free Gaza

692 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brennan can not help himself with the bird facts.

#freddie wong laughing during the woodpecker facts because he knows his character would be making rude comments if he were there is so great#brennan and hank green having a science-off is so fun#it was a stroke of brilliance to enlist hank for this season#how either of them have the brain space for this i'll never know#mentopolis#dimension 20 mentopolis#d20 mentopolis#dimension 20#d20#brennan lee mulligan#hank green#freddie wong#danielle radford#dropout#dropout tv#college humor

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The four players on dndads each fall perfectly into the four ways of playing dnd

Matt: uses the mechanics to play pretend real hard in a way that is most beneficial to the group

Beth: is perfectly in tune with her character and makes very good, compelling character choices that are sometimes v upsetting

Will: is trying so hard to kiss his friends in fiction will someone please just give this guy a break

Freddie: playing 4-D chess with himself in a way that makes me cackle at his shenanigans

#dndads#dungeons and daddies#dndads spoilers#matt arnold#beth may#will campos#freddie wong#freddie finally figuring out how to play a ranger right before Anthony offers to let them respec is v funny to me#but the moment he figured out how to get a +15 to stealth i knew. hes not gonna change#this is an appreciation post for all of them#and let me just say theyre all able to move between these archtypes and stuff and theyre all so good at their characters

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

The RE4R writers are funny

#resident evil#resident evil 4#resident evil 4 remake#re4#re4r#re4 remake#luis serra#ada wong#leon kennedy#separate ways dlc#separate ways spoilers#separate ways#my fanart: re#comics#comic#how am I supposed to interpret that line hmmmmmm

966 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sketched these raging bisexuals while waiting for Separate Ways

I'm NOT prepared

#FIRST POST OH GOD#ada wong#luis serra#emo nae nae baby leon#serennedy#i guess#raahhhhh#i dont know how tumblr works#leon on the froggy chair art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay so I just woke up from a 4hr nap wanting to talk about Leon for a bit. Emphasis on just woke up, so expect my thoughts to be jumbled.

To be honest, the more I think about this specific post (and the quotes that came with it) the more I don’t get how people can say that Leon is a “MEAN guy who’s actually really corrupt and morally grey” when in fact…

He didn’t hesitate to protect Ada from getting shot. He was gentle with her—despite revealing later that he did not trust her that much—and mourned her ‘death’ even after she pointed her gun and betrayed him. He only knew her for a day.

He sacrificed himself and started working for the government in order to protect Sherry. He didn’t have a choice, but he also said that he didn’t regret it. He only knew her for a day as well.

He comforted Ashley after seeing how terrified she was from being controlled by the virus. It must’ve been scary for him as well, realizing the unpredictability of the Los Plagas infection, but nevertheless he prioritized in making her feel safe and reassured. She was his mission, but he didn’t treat her like a mission—he was warm and friendly with her.

He mourned Luis’ death. He lit up his last cigarette and patiently listened to him talk about his regrets. He held his hand tightly. Despite knowing he worked for Umbrella—the very company that ruined his life—he sympathised with him.

He refused to give the chip to Claire in order to protect her. Some think that his decision was made because he wanted to ‘protect the government’, but it doesn’t take much to understand that he knew and understood (ex. Shen May’s situation) that Claire’s life will be in danger if he gives the chip. She is his dear friend—one of the only people who understood what he’d been through in Raccoon City—he couldn’t bear to lose her.

(Extra: I haven’t read the Infinite Darkness comic but this post mentioned that Leon made time to visit an injured detective he barely knew in the hospital and even asked the condition of two other guards.)

There are a lot more instances in other installments that showed Leon’s unwavering kindness, but I’ll stop here since it’s almost 4AM and I need to get ready for work.

Resident Evil isn’t particularly known for its story and writing, and there are a lot of inconsistencies and shit, but one of the things that stayed consistent all throughout the franchise is Leon Kennedy’s need to protect the people around him. It didn’t matter if he only met them for a day or they’ve wronged him. If he could just save one more life, he’d gladly push himself to the limit (and that is his biggest strength… and flaw).

Some people love to perceive him as either: a lovestruck fool who is a puppy for someone, or a man who is a mean jerk… but all I see is a man whose heart is so wounded yet continues to fight and give protection to those who need it. He may be working for the government now (by force, by the way; he didn’t have a choice), but that genuine part of him hasn’t changed, and will not change.

#finally letting this out of my head. can i just say that i cannot fathom how retwt works sometimes#most of the time actually. leon has been one of the more genuine characters of the franchise. claiming him to be morally grey is… weird#unless im missing something. ive always seen leon doing things not for personal gain or anything. he just wants to save people.#leon kennedy#leon s kennedy#ada wong#sherry birkin#ashley graham#luis serra#claire redfield#resident evil#adorathoughts#analysis

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

on death and rebirth

Ottessa Moshfegh My Year of Rest and Relaxation / @fadedkawasaki / 重庆森林 Chungking Express (1994) dir. 王家卫 Wong Kar-wai / Saeed Jones How We Fight for Our Lives / Katie Maria The Memory of a Memory / Ursula Le Guin Dragonfly; The Tales from Earthsea / 벌새 House of Hummingbird (2018) dir. 김보라 Kim Bora / pinterest

#on self#web weave#web weaving#poetry compilation#poetry parallels#ottessa moshfegh#my year of rest and relaxation#chungking express#wong kar wai#saeed jones#how we fight for our lives#katie maria#the memory of a memory#ursula le guin#the tales from earthsea#house of hummingbird#kim bora#poem#spilled poetry#spilled thoughts#writing#spilled ink#dark academia#words#dark academia poetry#dark academia quote#poetry#spilled feelings#spilled words

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

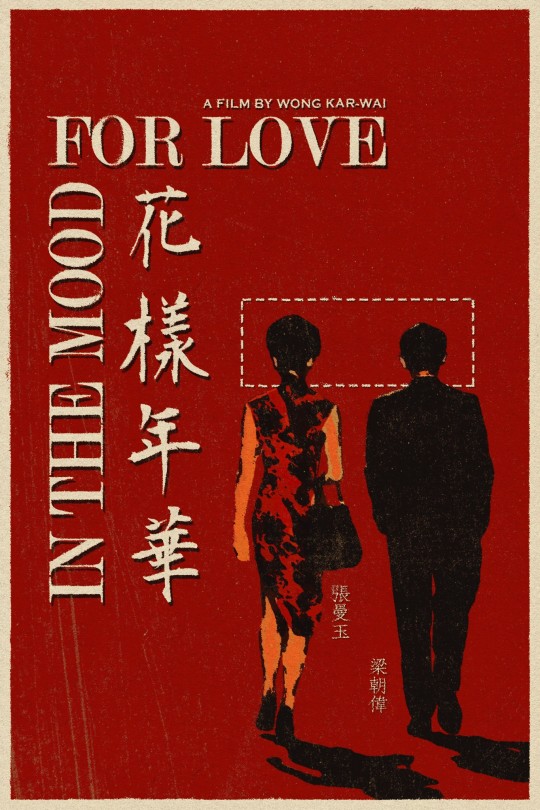

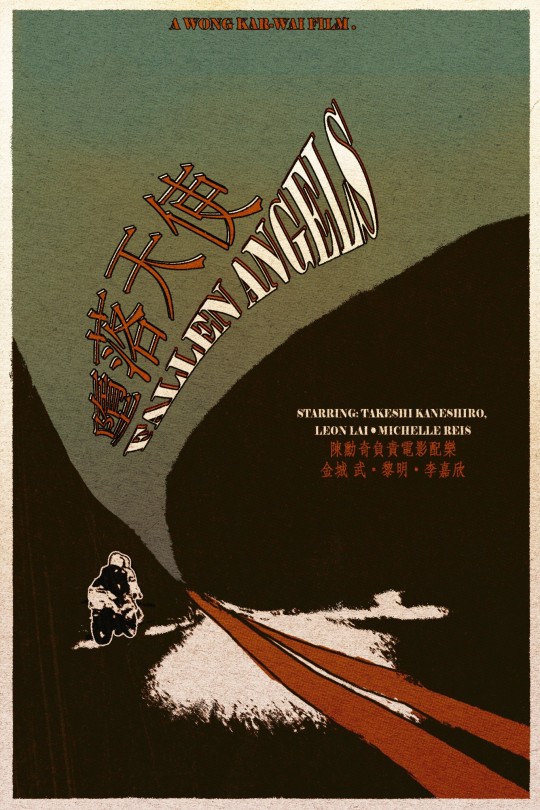

Wong kar-wai posters by me <3

#fallen angels#in the mood for love#wong kar wai#maggie cheung#tony leung#takeshi kaneshiro#idk how the formatting on this ends up being since I'm on mobile#by me

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

First post of 2025 HAPPY NEW YEARS!!!

#I made this in half an hour at like 3 am Ik how messy it is show me mercy………….#ericsart#resident evil#serennedy#leon s kennedy#luis serra#ada wong#ashley graham#leon kennedy#luis serra navarro#luis sera#luis sera navarro#leon scott kennedy#leon kennedy fanart#leon s kennedy fanart#luis serra fanart#luis sera fanart#ada wong fanart#ashley graham fanart#resident evil fanart#serrennedy#serrenedy#serennedy fanart#resident evil 4 fanart#resident evil 4 remake

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

shut up shut up shut up this pic is SO CUTE

LOOK AT HIMMMMMM

#crying rivers of devastation#how does he do it#pls give him hot choco and a hug#jack and joker u steal my heart#jack and joker the series#jack and joker#jack & joker#jackjoke#jackjoker#yinwar#yin anan#yin anan wong#war wanarat#wanarat ratsameerat#thai bl#thailand#bl series#bl drama#thai bl drama#thai drama

385 notes

·

View notes